Tell us a story

Your story should have a beginning (Introduction), middle (Methods and Results) and end (Results and Conclusions). Okay, so it’s not exactly ‘and they all lived happily ever after’! More like, ‘this work warrants further investigation’ and the characters wander off into the sunset in search of the elusive grant.

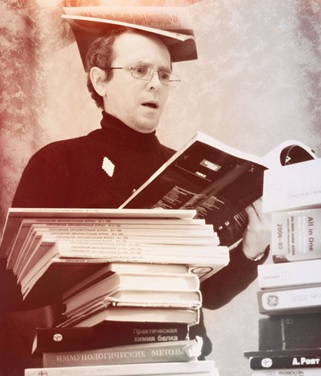

I’ve read more papers than I care to remember. I say ‘read’ in the loosest possible sense of the word. Some of the papers which I needed for my thesis and further research were dealt with in a vulture-like manner, stripping nuggets of information from the bones and body of the work (obviously in a manner which does not plagiarize). You know the sort of thing- you’ll read a review article and in amongst the thousands of words there’ll be that single sentence which confirms results you’ve seen.

A written word niche

Each and every one of us will develop our own writing style and this will be influenced by our work environment (and to a greater or lesser extent your mentor/professor/supervisor), but also by our environment of the written word in which each of us inhabits our own unique niche. No two people will ever read the same combination of blog/newspaper/journal/textbook/novel/comic. And, unfortunately, some of us may not even read for pleasure.

Reading for pleasure vs reading for work

When I was doing my PhD, it really turned me off reading for pleasure. Similarly, when I moved into different areas of research, the steep learning curves meant that I had to read another ton of articles. Reading for work really put me off reading for pleasure.

During my early career, I was an avid book worm. I would consume at least one novel or non-fiction book a week. I was living in the time of a new Scottish renaissance of writing with authors such as Iain Banks, Alasdair Gray, Irvine Welsh and AL Kennedy. At the same time, popular science books were really taking off- we’d had the early works of Richard Dawkins and the like, but now publishers were releasing books on topics ranging from viruses to quantum physics.

At this stage, I wasn’t required to read many papers or write a huge amount. I was running assays, gaining a grounding in histology and microscopy, trying (and failing!) with in-situ hybridisation. I had my name on posters, papers and abstracts, but merely as the person who had carried out the work. As my career progressed, it came with the expectation that I would start to contribute sections to publications. I started with the easy stuff- writing methods. As I was the one doing the work, this was no great hassle. However, it meant that I started reading more journal articles to examine and explore different styles and to try to replicate the way in which information is expected to be imparted to the readership of each of the journals. As I spent more time reading articles, it naturally meant less and less time for the books which I cherished.

To visualise and imagine

In my opinion, one of the most important aspects to being a good scientist is your ability to visualise and have a good imagination. Anyone with a reasonable memory can learn and regurgitate pathways and processes. But having a good memory doesn’t preclude that you have an understanding of the workings and mechanics of cells, biology and organisms.

I like to think that I have a reasonably visual imagination. I have absolutely no proof of this, but it may be partly due to the fact that I grew up reading comics and have continued to do so to this day. Comics are still regarded by some as ‘childish’- but, there are a large percentage of comics which are written especially for adults and mature readers. Some studies have shown that when we think like children, we are actually more creative. So, perhaps my years of reading comics has created a more visual and imaginative network in my neurons.

It was when I embarked on my part-time PhD that both my time for reading, and the material that I read was substantially narrowed. I had moved into a new field of research and facing the near vertical wall of learning a new area, I read very little else apart from journal articles.

Read far and wide and see the big picture

As you become more and more embedded in your own field of research, it can be difficult to see over the edges and to see the bigger picture. It’s an easy trap to fall into. If possible, try to continue reading for pleasure and reading around the edges of your own specific field. It all helps to see how your relatively tiny area of work fits in and can make a difference to the world- and the way you write.